|

all photographs can be clicked to access a larger version

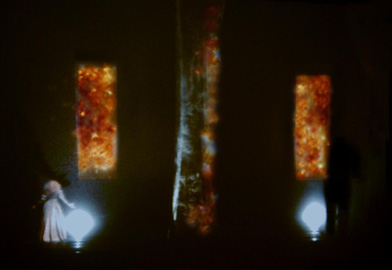

The Empress and nurse in a celestial world.

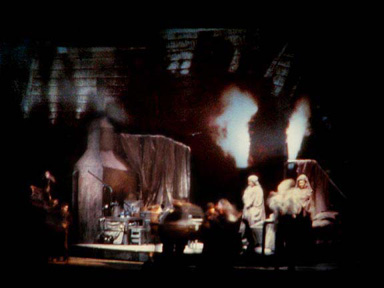

Richard Strauss' DIE FRAU ohne SCHATTEN (The Woman Without a Shadow) opened at the Chicago Lyric Opera in November of 1984 following a year and a half of production work by Chase and his craftsmen and film technicians. The production was again a departure from tradition, and Corsaro and Chase set the work during the period of the Industrial Revolution in Germany rather than in the fairytale milieu in which it often takes place. The Emperor's kingdom was seen as a world of geometry in which cubes and triangles served as projection surfaces. Some burst into flames, others glowed with mysterious lights.

The Dyer's hovel floats in a starry night.

The flaming triangle becomes the face of Keikobad.

The Empress and her nurse arrive in disguise at The Dyer's house. The stage is covered with smoke.

The Empress, played by Eva Marton, sang her most famous aria lying flat on her back, on an invisible platform suspended twenty feet above the stage floor while the film which brought the Empress to earth hurled viewers down a spiral staircase past smoke-spewing factory chimneys into the smog-filled streets and overcrowded living conditions. The Dryer's grotto appeared as a long transparent column of water up which the bodies of drowned men floated. In one scene, Barak's house was suddenly transformed into a golden palace. In another, into a boat sailing under a star-filled sky, and in another, a storm broke the house in two and sent its inhabitants hurtling into the air.

CHICAGO SUN TIMES: The Lyric—and the public—welcomed this production as a masterpiece. The production placed primary emphasis on projection. From the first moment to the last the stage is filled with a moving light, and this creates an entirely appropriate setting for a its drama. Ronald Chase's designs become an integral part of everything that happens.

The Empress dreams suspended in the air high above the stage floor.

In the storm, the house splits apart and the inhabitants are thrown into the air, some bursting into flames.

The Dyer and his wife in a space divided by a column of water where dead bodies float from beneath the stage to the flys.

The Grotto is transformed by light.

CHICAGO TRIBUNE: The new production must be one of the most visually inventive ever seen at the Opera House. This Frau works as beautifully for the eye as it does for the ear. It's projections and films whisk the viewer back and forth between the opera's two worlds, the spiritual and the human. Great swirls of smoke filled the front scrim. Elevators carried the singer up and down. Several scenes were magical enough to beggar the mind's eye. If Corsaro and Chase consider this an elaborate fairy tale for adults, they could not have chosen a more spectacular manner in which to present it.

MUSICAL AMERICA: As a compelling example of lyric theater this production was a standout. It moved with the speed of light, and the projections and film covered every surface imaginable, on scrims, on an airborne pyramid, on geometric shapes, through transparent plastic. The images ranged from a glowering, moving face of Keikobad, the ruler of the spiritual kingdom, through an impressionist forest with shimmering reflections of the Falcon's wings, to an Industrial Revolution of belching chimneys and gloomy factories surrounding Barak's earthly shanty. The harem vision resembled a sunlit Monet facade. The supernatural storm swirled the performers on turntables, then yanked them aloft on flying rigs and held them suspended in midair. The grotto scene divided the darkened stage with a transparent tubular shaft of light through which inanimate bodies rose from beneath the stage to the flies. It was a virtuoso optical feat which added dimension to the score without inundating it in the customary scenic elaboration.

|

|